How to Win in 2026: Intentional Experimentation

As we enter 2026, we face two somewhat opposing dynamics. On the one hand, there is massive uncertainty – tariffs, political polarization, economic volatility. On the other hand, we have massive opportunity. Generative AI can enable us to learn faster and produce more than ever before. But what worked in the past may not work in the future.

With these underlying forces in mind, I recommend making 2026 a year of intentional experimentation.

Let me offer the metaphor of GPS. Many companies have long-term growth goals. Let’s call this the destination. We know the address. What we don’t know is the best route. There are endless routes to that destination: scenic back roads, the highway, state roads.

In times of less uncertainty, we might have done a multi-year strategic planning exercise to determine a route at the outset of our journey and stayed the course. Today, the pace of change makes that course unwise. Instead, we need to check our GPS regularly to reevaluate. The GPS is our experimentation plan. It’s our regular check-in to ensure that there isn’t any new traffic, speed checks, construction, or detours. We need to keep checking our GPS, not because we’re lost, but because the road conditions keep changing.

Why Most Growth Plans Fail

The path to growth is never certain, but we can increase our chances of success. While working with companies to build growth strategies, I’ve noticed that the identified sources of growth are often not grounded in data: they are hypotheses based on gut or anecdotal evidence. I see two common approaches that result in suboptimal growth.

Buckshot approach: Chasing everything because it seems like a good idea results in:

Fragmented resources

Overwhelm and burnout among teams

Lack of quality or depth

The buckshot approach is never really picking a route. It’s constantly switching lanes, getting on and off the highway at the first sign of traffic, and winding through backroads from memory—never sticking with a route long enough to see whether it will get you there fastest.

Early overcommitment: Determining the route before the signals are clear:

Creating a multi-year plan without room for change and modification

Overinvesting in people, technology, and equipment before there’s a clear indication of success

Overreliance on gut vs. data

Lack of team buy-in and confidence, leading to constant questioning

The early overcommitment approach is like picking one route on a paper map and never checking your GPS to see when you’ll arrive, whether the roads are still there, or if there’s a faster way.

Whether you’re a new business or an established business trying new things, you don’t know what’s going to work, and yet you can’t do everything. Intentional experimentation resolves this tension and maximizes your chances of success.

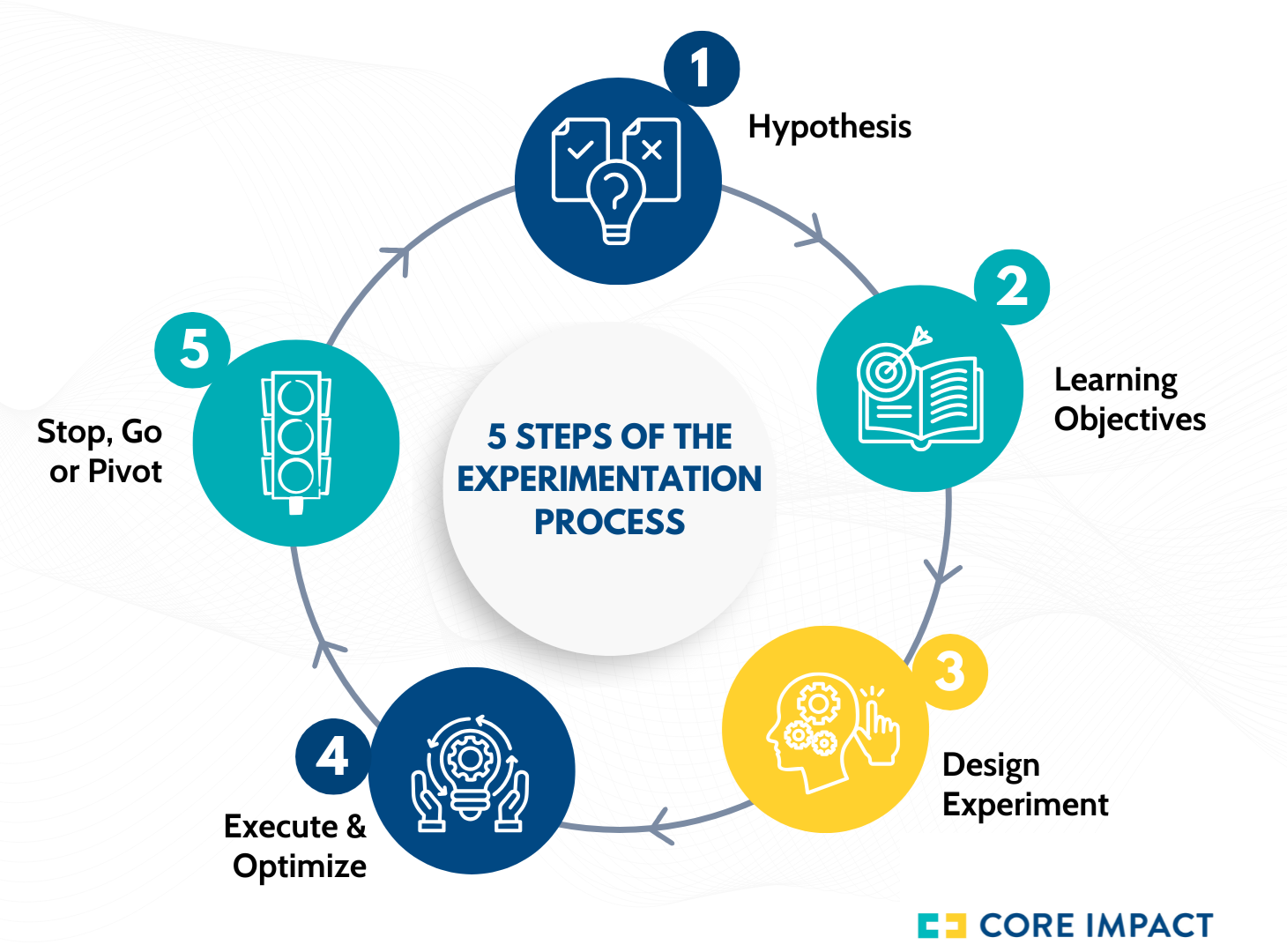

5 Steps of the Experimentation Process

Experiments help us ensure we’re on the fastest route.

This approach builds on the scientific method, which has been frequently used by business teams, especially in tech start-ups. I have modified these steps from frameworks such as The Lean Startup Method by Eric Ries.

This method can be applied to any growth opportunity at any stage of development and any size of impact. The key is to identify metrics that give us confidence we will have in-market success, and to design an experiment to gather those indicators.

In each of these steps, I have included several examples relevant to growth and marketing, but this experimentation framework can be applied to any new approach.

1) State your hypotheses

Do this by answering these questions: What do you think is going to happen? What bet are you making with this approach? We act because we think it will deliver results, but we don’t always specify our expectations. For example:

We think launching this product will help us acquire lapsed category buyers.

We think this marketing channel will make us more top-of-mind among our ideal customers.

We believe using AI to generate creative will increase the quantity of our creative by 25% and maintain the current quality.

We think targeting this market segment will increase sales by 10%

2) Define learning objectives and leading indicators

Your hypothesis states the ultimate outcome you want to achieve. Translating your hypothesis into a set of learning objectives and corresponding leading indicators can help you determine where to invest more resources. Leading indicators aren’t vanity metrics. Rather, they give you early confidence that your approach is effective. For example:

Do we have market interest?

Indicators: Qualitative feedback showing interest in buying a product or service in a new market

Does our message resonate?

Indicators: Repeat visits to your website; increased customers using your language in reviews and comments

Does this product delight our customers?

Indicators: Frequency of use, interest in repeat purchase, organic word of mouth

Does this approach increase conversion?

Indicators: Increased website conversions; increased rate of prospects converting to a second meeting

3) Design an experiment

Designing an experiment helps you decide whether or not to pursue a growth opportunity. Design the experiment to give you the leading indicator data. The scope must also be clear because, as you optimize, it’s helpful to know what modifications are in vs. out of scope. You don’t always need to have robust metrics and tracking systems. Here are a few examples with varying levels of rigor:

Interviews: Seek in-depth responses from 10 people to test a specific assumption

Test Market: Launch in one constrained environment—one geography, customer segment, or retailer—to understand market interest, messaging or pricing

Pilot Project: Run a project with a few customers to evaluate feasibility, systems, cost, and delivery capability

Message Assessment: Create a single message (e.g., one landing page, an email, or a sales deck) to test message resonance

Channel Sprint: Execute a specific and repeated set of activities in a limited timeframe to evaluate channel fit

4) Execute and optimize

I prefer to run experiments with frequent analytics and optimizations. Learn as you go, adapt quickly. If you get poor results, do something different that helps you answer your primary learning objective. For example:

Change the message

Talk to a different prospect

Try a different channel

5) Stop, go, or pivot

When an idea is a homerun, the decision to move forward is obvious. What’s more difficult is when the picture is less clear. Pursuing a path with mixed results is a recipe for mediocracy. Sunk cost fallacy is a major barrier to progress. Having the courage to stop doing one thing in search of another can unlock focus and growth within the team. Ask questions to determine whether or not it’s time to move forward. For example:

Did I gather all the data I need?

Did we achieve our success criteria?

Does the team still think there’s potential even though the results are bad?

When to use this framework

This plan only works if it’s integrated into your business’s operating rhythm. Even when using GPS, if we don’t have the volume on, we often miss a critical turn. Similarly, we need to build reliable systems that force us to experiment.

Integrate this framework into your annual planning. Identify your hypotheses—the strategies or investments that are more of a guess than a market-informed approach. Then, experiment. Document. Prioritize. Test your ideas sequentially, not simultaneously. If you have quarterly or monthly strategic planning reviews, consider adding experiments as a regular topic.

The leaders who will thrive this year won’t be the ones who lock into a rigid plan, nor the ones who chase everything at once. They will be the ones who do less but learn more.